Suzyika Nyimbili is a doctoral research fellow with the Higher Education and Human Development Research Group at the University of the Free State in South Africa. His doctoral research centres around higher education, cultural capability and human development. He is a recipient of the 2024 Human Development and Capability Association Ul Haq Scholarship and 2018 Mandela Washington Fellow. Suzyika is also a playwright, theatre maker, and founder of the Hub Theatre Company in Zambia. He is interested in researching and creating performances around African history, politics and memory.

When people hear the term intangible cultural heritage, many still assume it refers to witchcraft or outdated traditions with no place in modern society. This misconception has not only limited public understanding but has also created barriers for those studying or practicing ICH. In Zambia, for instance, it’s not uncommon for a degree in intangible cultural heritage to be mistakenly viewed as a degree in witchcraft, a reflection of deeply embedded colonial narratives and religious tensions.

However, ICH is far from being about superstition or the occult. It includes the vast spectrum of living traditions, languages, oral histories, performing arts, rituals, craftsmanship, and knowledge systems that communities pass down from generation to generation. These are not relics of the past they are living, dynamic parts of who we are today.

Safeguarding intangible cultural heritage is about identifying, documenting, and supporting these practices so they’re not lost in the fast-moving tide of globalization. It involves working with local communities to preserve their stories, languages, ceremonies, and customs in ways that respect their origins and cultural significance.

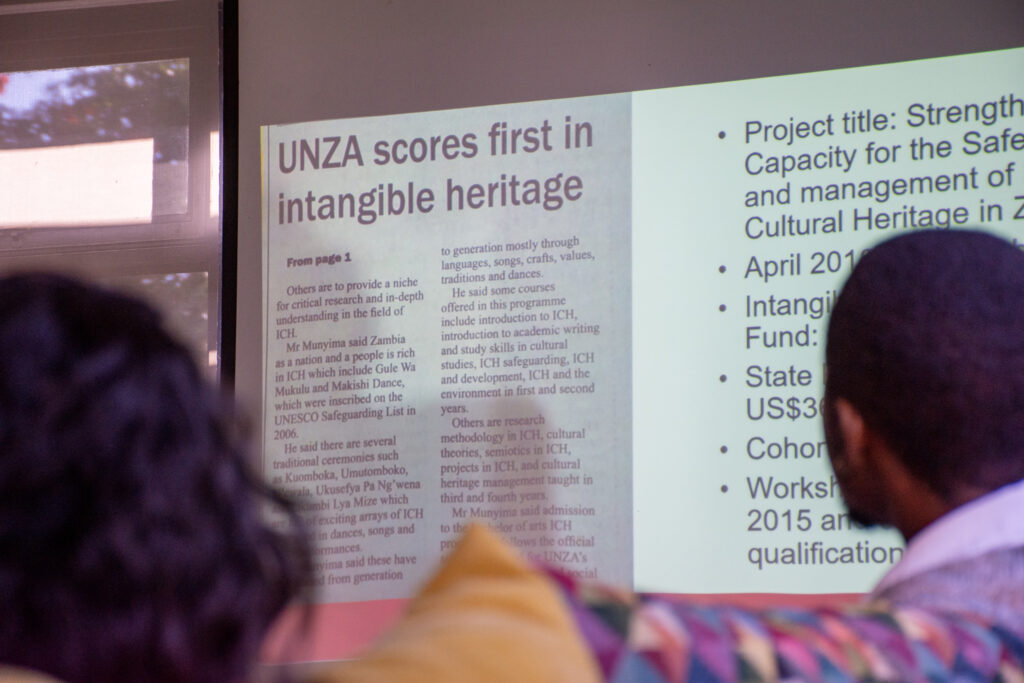

This presentation addressing this topic powerfully challenged the harmful stereotypes surrounding ICH and emphasized that preserving it is not about resisting change, it’s about recognizing value. The presentation explored how academic programs dedicated to ICH can play a pivotal role in capacity building, leadership development, research, technical support, advocacy, and community awareness.

There is growing interest in situating ICH safeguarding within higher education through degree programs and academic research. Such programs offer valuable capabilities, including:

- Deep cultural knowledge and awareness

- Practical ICH safeguarding skills

- Resourcefulness and creative thinking

- Opportunities for collaboration and recognition

- A renewed sense of cultural identity and aspiration

But this effort is not without challenges. The university as an institution is often shaped by rigid structures and western-centric models of knowledge, making it difficult to create space for indigenous knowledge systems. There’s a tension between academic frameworks and local ways of knowing especially in societies where Western knowledge is still upheld as the default, and traditional knowledge is dismissed as “backward.”

Our perceptions of culture and heritage are heavily influenced by colonial conversion factors the ways in which we’ve been conditioned to value foreign concepts over local ones. For example, in language, there’s often a preference for terms like “uncle” over culturally-rooted alternatives like yama or adada. Even in popular culture, words like “bally” gain traction because they carry a certain Westernized cool factor, sidelining more indigenous expressions.

This isn’t just about semantics it’s about power, identity, and how we define ourselves as Zambians.

In a country that strongly identifies as Christian, the association of ICH with witchcraft adds another layer of complexity. Many community members feel that traditional practices conflict with their religious beliefs creating a perceived divide between “light and darkness.” This belief system, though understandable, creates a major hurdle for ICH recognition and support.

On another note one of the most damaging myths is the belief that UNESCO simply handed over funding for ICH programs. In reality, the university and advocates fought hard to gain recognition and support for these initiatives. The progress made was the result of local effort, strategic advocacy, and an unwavering belief in the value of Zambian cultural heritage.